I was young once. Now, I am a boomer. When I was growing up, I never knew any child with a food allergy. Allergies of any kind seemed rare. Yet now, allergic concerns are frequently encountered? Just a few weeks ago, I was on a flight from Phoenix to Philadelphia. Shortly after the flight began, the flight attendant announced that no nut snacks would be passed out with in-flight drink service since there was a passenger on the plane with a peanut allergy. After I got over my shock that there might have been any snack at all, I reflected with surprise on the notion that the allergy of this person was so severe that any peanuts anywhere in the cabin was a threat. I had come into contact with thousands of children while growing up both as classmates and friends and I had never ever seen any allergic reactions. We all ate the same foods and there were no dietary rules. What is happening? What is different? After all, just think of it,…. how many boomers ever had a friend with a gluten allergy?

The answer to this apparent disconnect may lie in the emerging science of the hologenome and our contemporary fastidious cleanliness. Current research has suggested that the surge of allergic symptoms is related to our attempt to distance ourselves from our ubiquitous microbial companions. This has been dubbed the “hygiene hypothesis.” In theory, as we seek to protect our young from dirt and disease, we are inadvertently causing an imbalance in our vital exposure to microbial companions that are imperative for our optimal health. New research is showing that we live in an exquisitely intimate association with a vast collection of microbial life. This partnership can directly affect our response to allergens. There is epidemiological evidence that supports this new perspective. Some studies strongly suggest that immunological diseases such as asthma and autoimmune diseases are less common in countries considered to be underdeveloped compared to wealthier nations. Interestingly, this same pattern sees to also hold for a variety of other chronic illnesses.

These microbial partnerships are essential to our metabolism, reproduction, longevity, and well being. This is now known as the new science of the hologenome. The concept of the hologenome re-envisions all organisms as a deeply interlinked complex partnerships between the cells that make us ourselves and our indispensable microbial partners. This has lead to a concept called the ‘old friends hypothesis’. As proposed in 2003, this theory asserts that there needs to be a requisite exposure to a variety of diverse microbes with which we were associated during our evolutionary journey. Therefore, our metabolism is dependent upon certain microbes, as ‘old friends’, and they have become absolutely necessary for our optimal immunological development.

In our zeal to protect against harmful infections, we have inadvertently shielded our children from the typical exposure to a diverse array of microbial life that had characterized all prior generations. The consequence of this exclusion from these vital exposures is experienced as a significant increase in allergic reactions such as hay fever, food intolerance and asthma. In theory then, a substantial increase in the incidence of allergy is a result of this restricted exposure to the microbial domain. All of these problems are thought to be an expression of a decrease in immune tolerance related to a significant change in how our children encounter the environment compared to previous generations.

It currently appears that allergic reactions of all sorts may be directly related to the inadvertent exclusion of critical microbes that co-evolved with us and are required for our personal microbial and cellular ecological balance. Medical practitioners are learning that our health depends on this striking balance of microbial forces. For example, recent research suggests that infants that are not fully exposed to an extensive group of microbes have a less diverse gut microbiome ( microbial species in the gut) and are at increased risk of allergies and asthma. A recent Canadian study provided evidence that exposure to pets and a large number of siblings influenced the early development of gut microbial community of an infant. Less exposure was directly implicated in the subsequent development of allergic disease.

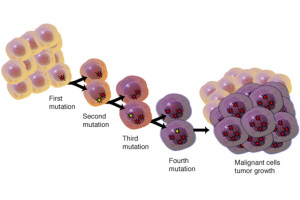

Some scientists believe that the lack of exposure of children to the normal distribution of microbial interchanges can have additional implications. Research studies suggest a potential association between this generational change in childhood experience and the increasing incidence of chronic diseases beyond asthma, food allergies or allergic rhinitis. Many immune centered diseases are potential related to this dynamic such as diabetes, multiple sclerosis, some cancers and even psychological entities such as depression or autism.

What then is an appropriate response to these concerns? Actually nothing special at all. If your child has been vaccinated, simply be willing to let your child share in reasonable unrestricted play with other children and share toys. And also, just let them roll in the dirt with a pet.

The Microcosm Within | Modern Theory of Evolution |

The Microcosm Within | Modern Theory of Evolution |