There would be no requirement that all of the exact constituents of the conjoined ecologies that make an organism stay static. Indeed, we know that they do not. However they do need to stay within biological boundaries or that exact species forfeits its place in a competitive landscape in which any organism is under continuous assault by a very aggressive external genetic milieu. This is the exact interface between health and disease for all complex creatures.

If this seems a bit daunting, it is so only at first blush. Nature certainly does not see us as singularities as the Darwinist have long believed. Instead, we are holobionts. There is no pore, orifice or hidden compartment within us that is ‘sterile’. That concept is now defunct. Importantly though, it is not that just some complex organisms are hologenomic beings. All complex organisms are, and there are no exceptions on this planet. So any coherent theory of evolutionary development must endorse that endpoint as its narrative.

Monthly Archives: July 2014

Neo-Darwinism and Modern Evolutionary Synthesis

Hologenomics: A Modern Theory of Genetic Evolution

All cells seek to maintain themselves within a narrow functional boundary. This is termed homeostasis and is a fundamental property of cells. Importantly, each cell can cooperate and collaborate as well as compete towards its goal of sustaining its best homeostatic moment.

From this, evolution proceeds by a dramatically different dynamic than by simple natural selection – genetic transfer, cellular intentionality and natural genetic engineering empower its course. Natural genetic or cellular engineering is the process by which cells constructively cooperate, collaborate and compete to sustain their preferred homeostatic level. In successive layers of interactive cooperation and competition, phenotypic novelty is built. Importantly, it is always an expression of the efforts of the conjoined cellular constituents to successfully maintain themselves. In this way, it is not really conceptually different from how we humans build cites. We each collaborate and cooperate and mutually compete to enact a city with all its forms and intricacies that in no manner resembles any individual human. We do this with the tools that we can employ in both the inorganic and organic realms based on our own privileged and still limited capacities. Cells do similarly but strictly according to their own limitations. They use what they can, which in their circumstances, are biological substrates. In an important sense then, we humans demonstrate capacities that are themselves direct iterations of base cellular faculties. We express them too, through our means, in a manner unique to our human species.

Critically then, the wondrous forms and biologic processes that we readily assess emanate from a process of cellular creativity. That creativity is enacted at all times to best maintain all of the cellular constituents within any localized ecology, and reiterating onward and outward towards the forms and functions that we can easily apprehend. This process is not merely random. It has the directional component of the self-awareness within cells, which can be termed ‘cellular ipseity.’ Random events still manifest. However, they are utilized as they can be or simply accepted if resistance is futile. That output however must be ‘fit enough to survive.’ It is here that natural selection operates.

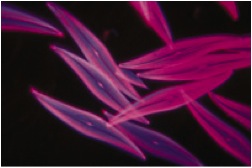

In the cellular realm, this engineering process is effected by genetic transfer mechanisms that are not haphazard but proceed along the lines of biologic interactions that have previously and casually been recognized as infectious disease dynamics, a new principle in biology and evolution.

Importantly though, the guidelines governing this process are immunological in nature. All cell-to-cell interactions are immunologically governed. In evolution, immunology rules.

Its yield then is just the end point that modern science informs us is our natural reality. All complex creatures are hologenomes. Not as exceptions, but as the only complex organisms on this planet. Any new theory must completely explain this biologic endpoint. How is this best explained by Hologenomic Evolutionary Theory? It alone is a theory rooted in cellular collaboration, cooperation, and co-dependence just as much as competition. It is a theory of connections, enacted cell-to-cell, layer-by-layer, and ecology-to-ecology. Evolutionary development is a building process through collaborative cellular dynamics and not merely a whittling process through natural selection. In Hologenomic Evolution Theory, connections are built upon the discrete and omnipresent primordial awareness of cells and genetic aggregates. Every biologic process that can be witnessed is its current expression.

For all its varied contortions, Darwinism is deeply rooted in Victorian sensibilities … competition through natural selection… ‘Survival of the Fittest.’ In contrast, Hologenomic Evolution Theory asserts that complexity and novelty are acts of cellular creativity to serve the limited and discrete needs of constituent cells in an endless series. Genes are a form of communication as well as reproduction and act to sustain the varied environments and collected ecologies that comprise any complex organism. In this manner, genes primarily exist to ‘serve’, another important difference from Darwinism. Despite our prolonged Darwinian detour, fresh scientific findings are confirming that our evolutionary narrative has been affected through the demonstrable capacities of cells and the immunological reactions that govern their world.

Mass Extinction Events Diffrentiate Patrick Mathews’ Work from Darwin Evolution Theory

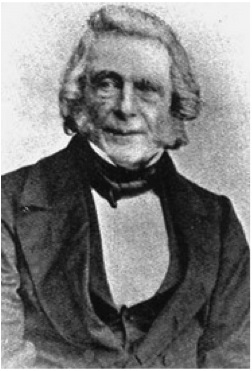

Interestingly, Darwin was not the first to propose evolution by natural selection. New York University geologist Michael Rampino argues that there was an earlier theory of selection and gradual evolution advanced by Scottish horti-culturalist Patrick Matthew in the 1831 book, Naval Timber and Arboriculture, prior to the publication of Darwin’s work.

As opposed to Darwin, Matthew saw catastrophic events as a prime factor, maintaining that mass extinctions were crucial to the process of evolution: “…all living things must have reduced existence so much, that an unoccupied field would be formed for new diverging ramifications of life… these remnants, in the course of time moulding (sic) and accommodating … to the change in circumstances.” This insight was remarkably prescient as it is generally believed that evolution is indeed best understood by long periods of stability interrupted by major ecological changes that can occur both episodically and rapidly as opposed to only continuous and gradual modulation.

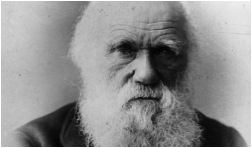

In On the Origin of Species, Charles Darwin skillfully advanced the concept that evolution proceeded by a process of gradual modification and that natural selection was its primary mechanism.

Even if not the first to consider these factors, he did contribute enormously. He put these concepts into a coherent evolutionary frame and defended it vigorously and well.

With new scientific discoveries, Darwin’s theories have been modified in an attempt to be concordant with new evidence. This has yielded substantial alterations of the purported mechanisms of evolution on a nearly continuous basis. Many of these same debates are in fact continuing. Aspects considered as conclusively settled at one time by some are reopened for discussion in the face of new discoveries. Consequently, issues involving the most basic processes in evolution that were nettlesome to Darwin such as blending or discontinuous inheritance, continuous evolution by gradual modification or by gaps, and differing viewpoints on the origin of organic complexity are still a part of our continued debate. However, Darwin’s looming presence has been a critical factor at every step.

The quintessential work of Charles Darwin, On the Origin of Species, wasn’t first among evolutionary theories

Another theory, Uniformitarianism, was propounded by Charles Lyell between 1830 and 1833. He asserted that the laws of nature are constant and immutable over time and space and that such laws could be identified and would account for evolution.

New theories abounded after Darwin, too. In 1893 William Haacke and the zoologist Theodor Eimer espoused Orthogenesis. They generally conceived of evolution as moving forward in a straight line and held to a regular course by non-random forces that are internal to the structure of organisms. These internal factors essentially propel an organism forward developmentally and selection is limited in scope.

The Vitalists in the early 20th Century proposed that evolution was driven by the fact that living organisms are fundamentally different from inanimate ones as they are imbued with an intrinsic ‘vital spark’ or energy. This was not a new idea and, in fact, it was an ancient doctrine that had been believed by many great scientists including Louis Pasteur. However, this concept was eclipsed by the rediscovery in 1900, by Hugo De Vries and Carl Correns, of the critical work previously done by Gregor Mendel, an Austrian friar and scientist who is considered the father of classical genetics. He had discovered by working with garden peas that the result of a cross between peas of different colors was not only a blend, but also yielded offspring of both separate colors in predictable ratios. He conceived of the concept of heredity units, which he called “factors” and were later called genes.

The rediscovery of Mendel’s work in genetics led to a variety of new proposals and theories and a division in perspective that this reverberates today. One school of theory favored viewing evolutionary development as primarily proceeding by large mutations or jumps, called Saltationism. Another opposing school, the Biometric school, advocated that variation was continuous and gradual in most organisms and favored a mathematical and statistical approach. Both were attempting to unite Darwinism with genetics and it is this latter approach that is embodied in what is termed the Modern Evolutionary Synthesis or current Neo-Darwinism.

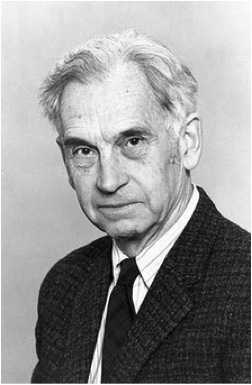

The development of population genetics as the study of genetic variation and gene distribution in populations under the influence of natural selection was pioneered by Fisher, Haldane, and Wright. Their work was fundamental in establishing many of the underlying principles of Neo-Darwinism. The Williams Revolution of the mid 1960s shifted thinking from population genetics models to natural selection via kin selection. In this model, the gene is the fundamental unit of self-preservation either by acting to protect and preserve itself or closely related genes. This was expanded by Richard Dawkins who popularized the concept of the “selfish gene,” a gene centered view of evolution with selection acting on the genes themselves and not only on organisms or populations. In this view, we are just genetic vessels or carriers.

Contemporaneous to Dawkins, the concept of endosymbiosis was widely popularized by Lynn Margulis in the 1970s although it had been proposed decades earlier. The underlying theme of ‘endosymbiotic theory’ as formulated as early as the late 1960s was that the evolution of eukaryotic cells (cells with complex structures enclosed by membranes) over millions of years was enacted by the interdependence and cooperative existence of multiple prokaryotic organisms engulfing and incorporating one another. Although originally dismissed as a fringe concept, it is now recognized as the key method by which some organelles have arisen.

More recently, Eugene Rosenberg and Ilana Zilber-Rosenberg presented research advancing the concept that the object of natural selection on genomes is not solely on the individual and its central genome but on the combination of a ‘host’ organism and the entire symbiotic community with which it is associated. From this concept of the hologenome, originally conceived by Richard Jefferson, an entirely robust and alternative narrative of evolution can be offered, Hologenomic Evolution Theory. In this theory, evolutionary development builds upon cellular interactions governed by immunological rules. Natural selection remains an important factor but is displaced from its central role.

Spread of Infectious Disease a Consequence of Climate Change

The single most pressing consequence of climate change, whether global or localized, will be in the shifting patterns and spread of infectious disease. Substantial alterations in temperature and humidity can directly relate to the distribution and

Support

Many researchers believe that this effect can be currently observed. For example, malaria[1] spreading to the highlands in Africa and the northward spread of West Nile Virus[2] in the United States has been linked to the changing distribution of disease-carrying mosquitoes relating to climate change. So, too, have shifts in the spread of dengue fever[3] in endemic areas.

A wide range of diseases are zoonotic in etiology so a shifting climate may enhance the likelihood of that cross-transmission or its virulence. There is evidence for just this type of consequential shifting pattern. Ecological variation has been ongoing over earth’s history, and that of man’s time on earth. Humans have been both victims of pathogens and carriers. For example, the loss of the North American large mammals like the woolly mammoth and saber-toothed tiger has been correlated by some researchers to a phenomenon termed hyperdisease[4]. In that instance, humans as carriers or our traveling companions, such as hunting dogs or domesticated animals, are thought to have introduced new pathogens or more virulent ones to an unprepared environment.

Response

How then should this affect our global response to climate issues? It must begin with increasing awareness among climate scientists and physicians. However, there should also be a redirection of scant available resources from unproved expensive projects of carbon capture and sequestration to productive research studying the patterns of communicable disease. This might mean evaluating and implementing better means of mosquito, tic, and rat control; sharpening our tracking of current patterns of communicable diseases; and aggressive research into improved prevention or therapies. All would yield substantial benefits with certainty, whether a shifting climate is consequential now or in the future.

–Bill Miller, MD

References

1. Bouma MJ, van der Kaay HJ. The El Niño Southern Oscillation and the historic malaria epidemics on the Indian subcontinent and Sri Lanka: An early warning system for future epidemics? Trop Med Int Health 1996;1:86-96.

2. Morin CW, Comrie AC. Regional and seasonal response of a West Nile virus vector to climate change. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2013;110:15620-15625.

3. Hales S, de Wet Neil, Maindonald J, et al. Potential effect of population and climate changes on global distribution of dengue fever: An empirical model. Lancet 2002;360:830-834.

4. MacPhee RDE, Marx PA. Lightning strikes twice: Blitzkrieg, hyperdisease, and global explanations of the late quaternary catastrophic extinctions. American Museum of Natural History. Accessed 13 June 2014. www.amnh.org/science/biodiversity/extinction/Day1/bytes/MacPheePres.html.

The Microcosm Within | Modern Theory of Evolution |

The Microcosm Within | Modern Theory of Evolution |